Crows are one of the few animals to show a social reaction to the death of individuals of their kind along with dolphins and elephants Although their cravings may seem like crying out of psychological pain, these funerals are not about mourning the dead of their friends but about learning from their mistakes.

“What killed this bird?” they seem to be thinking “And how do I avoid the same fate?”, according to a new study published in the Royal Society Publishing journal Philosophical Transactions B, Came titled "Occurrence and variability of tactile interactions between wild American crows and dead con specifics", For Kaeli Swift, an animal behaviorist at the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences at the University of Washington.

Over the course of two years, Swift tracked down pairs of crows across the Seattle area and submitted them to one of two controlled experiments, In the first trial, she presented each pair with one of several taxidermied corpses she kept in her backpack—either an adult crow, a juvenile crow, a pigeon, or a squirrel, In this study, she found that the majority of crows (70 percent) refused to interact with the dead animal—which makes sense.

There’s a risk associated with approaching a corpse, says Swift. You can contract a deadly disease, get mobbed by stinging insects, or perhaps get offed by whatever killed the other animal, This is why she and her coauthor John Marzluff , also of the University of Washington, believe crows perform these so-called funeral rituals, the animals are trying to learn about threats in the area.

However, in 10 of the 153 trials, Swift and Marzluff found that the birds threw caution to the wind not just to peck at the crow corpses or try to feed from them, but to engage in sexual behaviors, These include either mounting the carcass, engaging in sex with their mates near the carcass, or presenting themselves to the carcass (drooping wings, up tucked tail, vibrations, etc.) as though they were a potential mate.

This was odd, to be sure, but perhaps these behaviors could be explained by sheer confusion, Was it possible the crows didn’t know the dummies were already dead?

To find out, Swift scared up an entirely new roster of paired crows—she didn’t want to use the same ones in case the birds remembered her or the previous experiment and that skewed the responses, In the second trial, she presented the living crows with either a taxidermied crow that was laying on its side, as if road-killed, or a taxidermied crow that was propped up to appear as though it was still alive, Interestingly, the living birds seemed to be able to tell the difference, choosing to scold (or caw at) the dead-looking corpse more often and dive-bomb or mob the live-looking corpse more often.

But here, too, the crows came on to the corpses, Sexual events occurred four times with the life-like crows and eight times with the roadkill ed ones, What the actual heck?

According to Swift, the key to understanding this morbid behavior may be timing, Every single one of the interactions occurred during the birds’ breeding season, Though the birds interacted with the roadkill ed birds twice as often, Swift says the upright test wasn't performed as many times during this "sexy window.

They’re going through such intense hormonal changes as part of that breeding season, and they’re so excitable,” says Swift. “I think that their fore brain recognizes that this individual is not a threat that it’s not alive, but they’re so charged up that they get overcome in responding to that stimulus in a way that they would if it was alive.

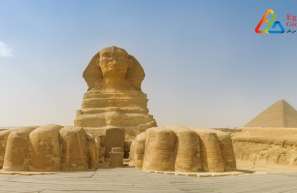

Egyptian Site & magazine