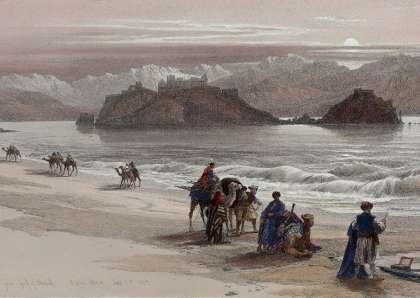

Ever since Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) briefly conquered Egypt in 1799, the French had been fascinated with the mysterious East as this distant and exotic place, holder of mysterious and ancient secrets, The psychological phenomenon of Othering an entire region is known today as Orientalism but in the middle of the nineteenth century, the Near East was a site of imperialism, “Orientalism” was a means of naming and thus controlling a region that could not be understood in its own terms but only in its relation to Europe.

It could be said with some caution that Maxime Du Camp was one of the first pure documentarians to attempt to produce a photographic project inspired by the empirical determinants of scientific research. His work falls in an uneasy zone between the “imperial eye” and the “camera eye”, According to what he confirmed Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History.

By 1849, the year Du Camp decided to go to Egypt, the country was ruled by Abbass Hilmi, the grandson of Mohammed Ali, who reversed the historical preference for the French in favor of the British. It can be assumed that Du Camp was less interested in contemporary international politics than in the ancient history and the harem beauties of Egypt.

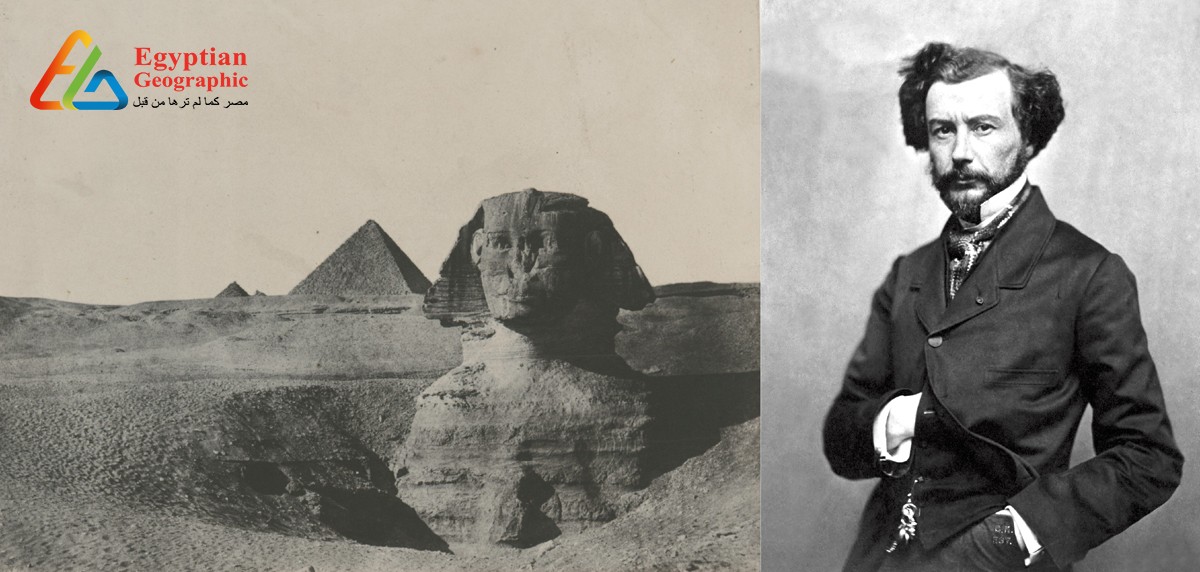

Already a world traveler who had written Souvenirs et Paysages d’Orient: Smyrne, Ephèse, magnesia, Constantinople, Scio in 1848, Du Camp had dedicated to his close friend Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), On this journey to Egypt, he decided to take a camera with him, an interesting notion, given that Du Camp was enamored with the Romanticism of Victor Hugo (1802-1885), But he was determined to make a photographic, rather than a literary journey, switching from a literary interpretation or a written Orientalism to a pseudo-scientific approach to Egypt.

In 1849 the Calotype process was still new to the French and Du Camp was not satisfied with Le Gray’s use of the paper process, and he learned how to wax his papers through the photographic publisher Louis Désiré Blanquart Evrard (1802-1872), But within a few weeks, Du Camp considered himself proficient enough to convince the French government to support a photographic tour of Egypt and the Holy Land, so was using a wooden Calotype camera and tripod, To ensure that images came out properly he had to bring along a number of chemicals required to print on writing paper for his negatives.

Du Camp was independently wealthy, but he approached the French Ministry of Education for its sponsorship, which would elevate the exhibition from tourism to science, His traveling companion and fellow Romantic enthusiast, the then fledgling novelist tall, blond, and handsome, Flaubert was so fixated on “the Orient” he considered this fabled land his spiritual home, but strangely enough he had been tasked by the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce to collect information for business interests.

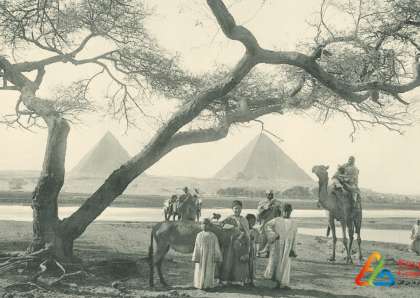

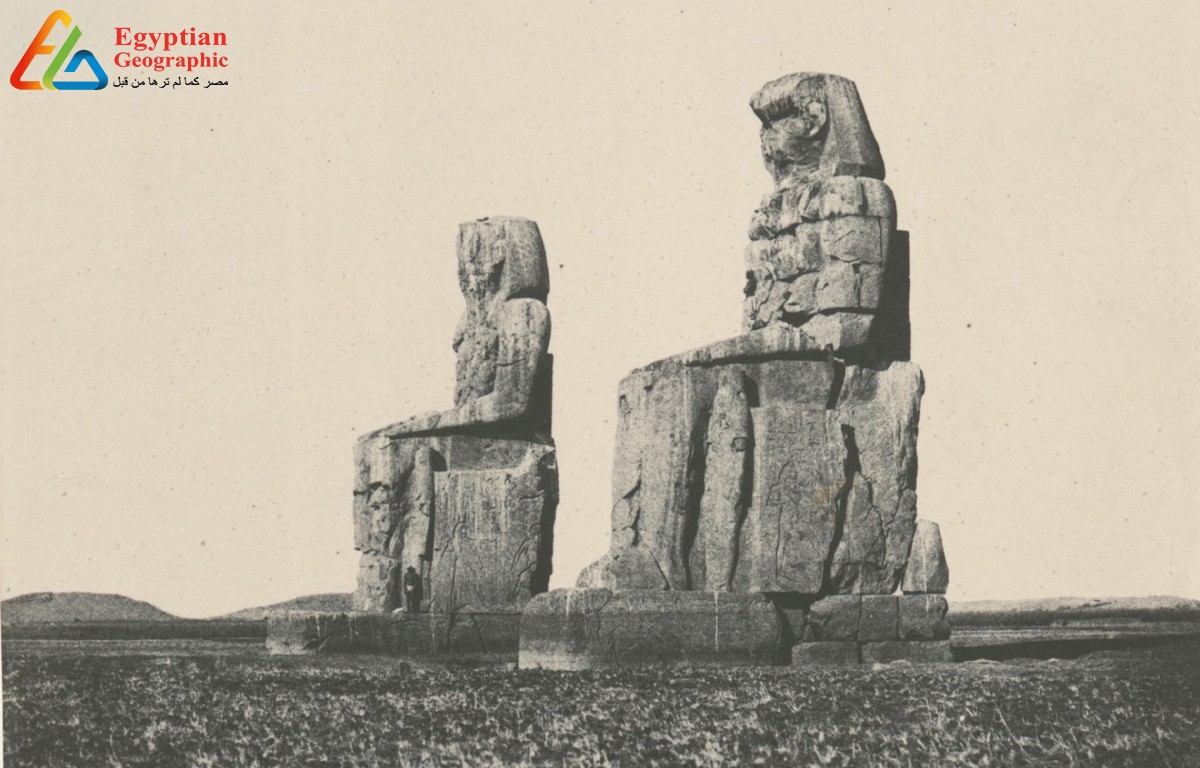

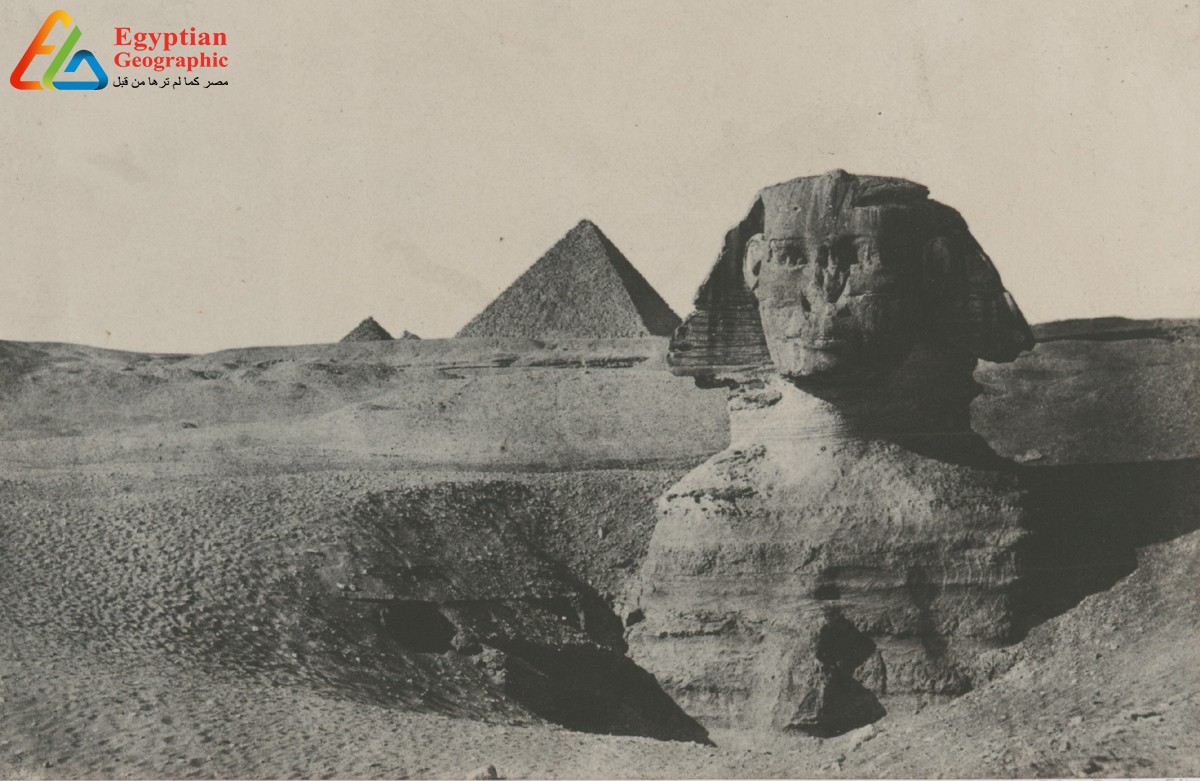

Both young men were rich and privileged and spent two years enjoying themselves as tourists, sexual adventurers and documenters of ancient sites, Accompanied by a young poet, Louis Bouilhet, and the languid Flaubert, the efficient Du Camp focused on photographing the pyramids, the sphinx and other Egyptian monuments, following a map marked with points of historical interests. In other words, it was his intention to record a tourist’s eye view of ancient Egypt in European terms, a romantic adventure already ready, packaged for the wealthy traveler.

Certainly this venture received so much governmental support because of France’s imperial interests in Egypt, Flaubert and Du Camp were well received by the Egyptians who still favored the French and were warmly welcomed by the newly installed Abbass, something that would have been problematic a year later, on their twenty-one-month tour.

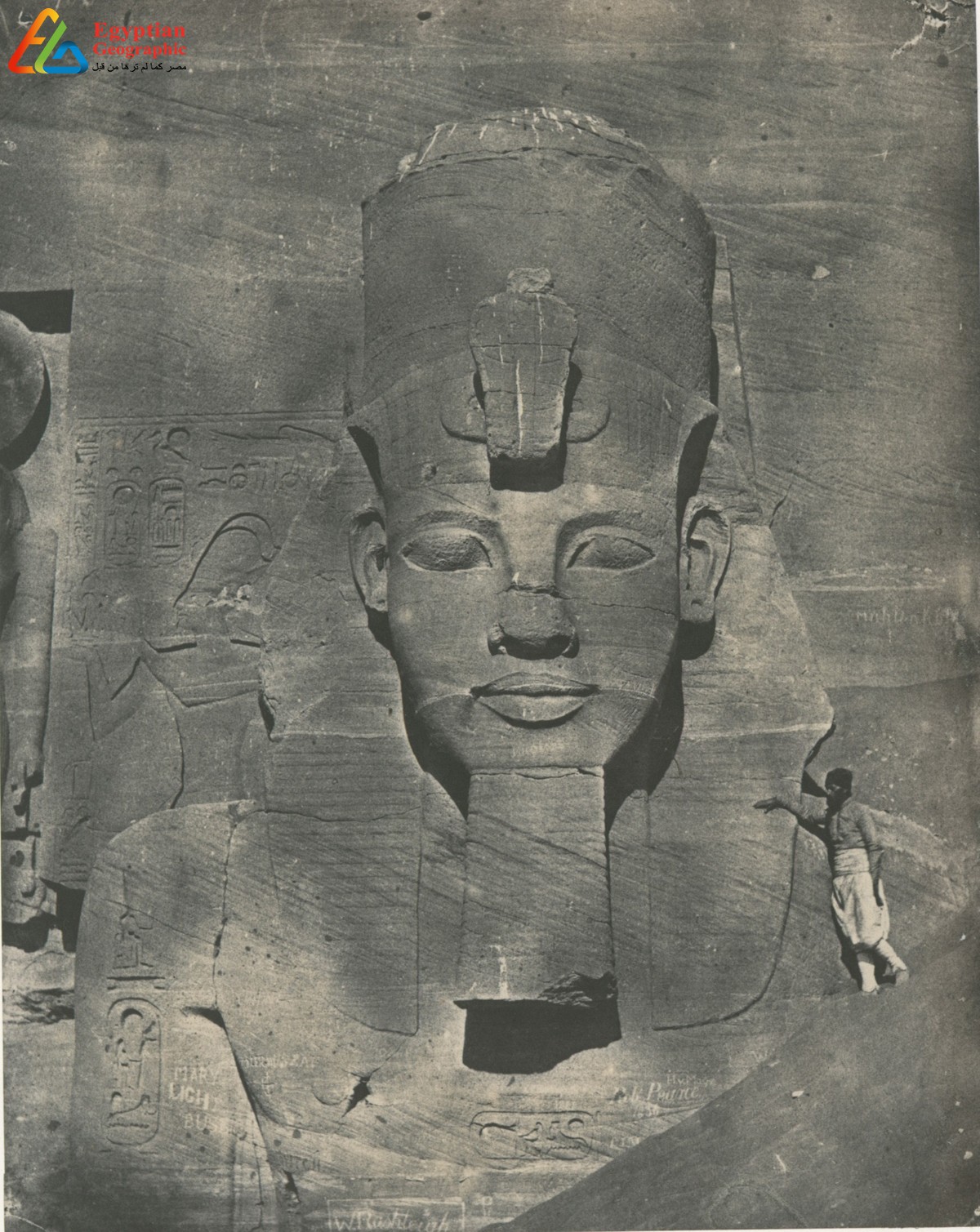

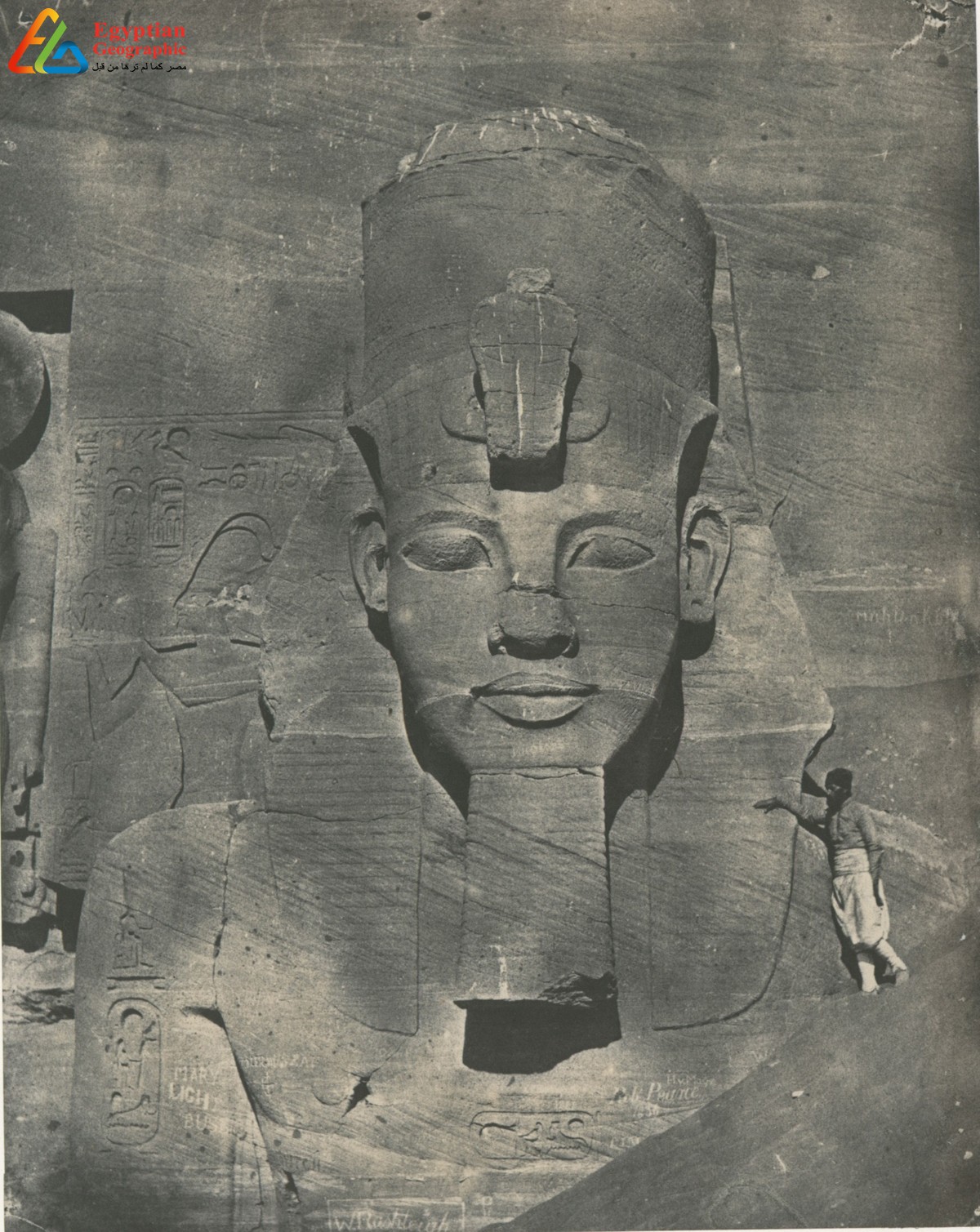

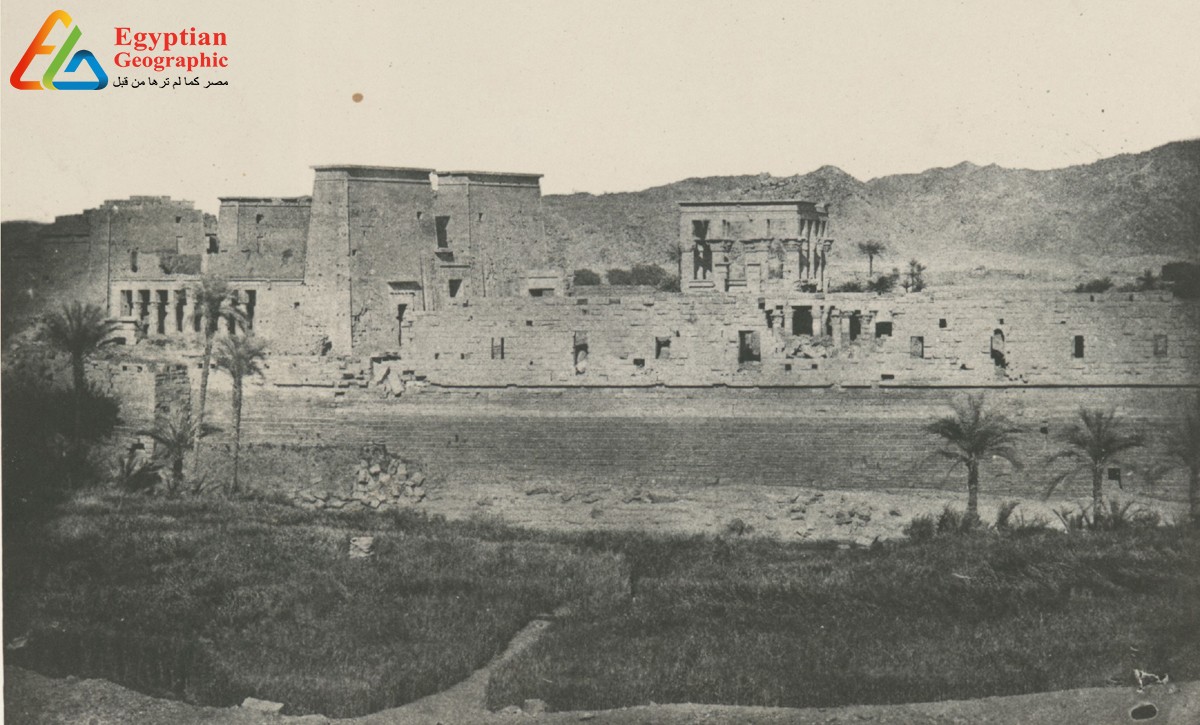

Du Camp, who worked systematically in an archaeological mode made two hundred and twenty Calotypes, wrote copious notes and educated himself on Islam, Many of his photographs of Egypt contain a figure of a male, Hadji-Ishmael, who served to give the French reader a sense of the scale of the monuments.

Du Camp observed everything and recorded as much as he could, as if to stop time and to freeze its passage, but whatever passion that drove his accounting, Du Camp allows the camera to do all the work. What we see in the photographs of the Near East is almost pure camera vision, alienated only by the occasional insertion of human figures for referential purposes, Certainly Du Camp could have asked for Flaubert, for example, to provide a human presence the fact that he did not imply that he used the young sailor in a de-humanizing fashion, as a human measuring stick, intended to provide information and to disappear.

It is clear from looking at Du Camp’s work that he may have been a photographer, he was an uninspired one, lacking any artistic imagination of aesthetic sense, Of course, unlike the Calotype photographers of France, he had no artistic training and through of photography as a camera recording ancient monuments from an archaeological perspective, For a devotee of Romanticism, Du Camp strangely scours his images of the mystery that so fascinated his time, A member of the Société orientele, he promised documentation and his images are seldom anything more than flat-footed. The image of the pyramid below is a rare attempt on his part to convey the “romance” of Egypt.

Du Camp had to continue his lessons in photography as he worked, the light in Egypt was much brighter than that of France and there were no light meters at that time, He had to guess and work by trial and error to determine the appropriate exposure time, an aggravating process of failure before finally achieving success. As Du Camp himself wrote, “If, some day, my soul is condemned to eternal damnation, it will be in punishment for the rage, the fury, the vexation of all kinds caused me by my photography”.

Du Camp’s struggles with the basics of photographing in Egypt would be characteristic of those suffered by photographers who came after him, As primitive as his paper photography may have been, the basic chemistry was an advantage over the more complex chemistry of the more “advanced” collodion process, Du Camp did not need a van to transport his equipment and his chemicals were not as inclined to boil over in the hot sun, The sheer difficulty of photographing in hospital climates could account for the rather small number of successful prints for two years of work.

When Du Camp returned to France he attempted to print out his own images but was plagued by problems of fading, Once again he turned to Blanquart Evrard for assistance and the printer took over the task and used albumen to fix the tones, In the end only half or one hundred twenty-five of his Calotypes were printed by Louis Desire Blanquart Evrard (1802-1872) and published in 1852.

Printed in an edition of two hundred high priced volumes, Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie was the first book about this area of the world to be illustrated with actual photographs, After his return, Du Camp put aside the troublesome camera and gave up photography, devoting his time to writing.

It has long been argued that Maxime Du Camp’s 59 images taken during an 1849 and 1850 trip through Egypt with the novelist Gustave Flaubert, are the birth of “travel photography.” Photography, as we traditionally know it, had only existed for about 20 years and was relatively new at the time.

Egyptian Site & magazine